“Should everything perish, all the books, the photographs and the documents, and we were left only with the woodcuts Masereel has created, through them alone we could reconstruct our contemporary world.” — Stefan Zweig

When asked about the Belgium artist Frans Masereel, the two thoughts that immediately come to mind are woodcuts and war. I do not know an artist who was so wedded to the woodcut in expressing his loathing of war. Although this theme prevailed in many of his books, an examination of his woodcuts in Debout Les morts (Arise Ye Dead, 1917) as reprinted in this issue of THE REVELATOR, provides a vital connection to his subsequent anti-war books; and there were many, as we will discover.

Masereel was born in 1889 in an upper-middle class family from Blankenberghe, Belgium. He showed interest in drawing and remembered a dislike of war from an early age:

I can still remember the Boer War, which made a great impression on me. How old was I then? Ten or twelve, perhaps thirteen? It was at that time that I began to make drawings, children’s drawings, of course, that were against the war, and ever since, I believe that I have always remained very anti-war (Avermaete, 17).

He studied at the Academie of Arts in Ghent in 1907 where he met Jules de Bruycker, who Masereel declared “taught him to see and to draw” (14). He left school after a year and a half and travelled to Paris and Brittany where he continued to draw and paint. It was during this time that he submitted drawings to the satirical magazine L’Assiette au beurre, published by Henri Guilbeaux, who became a lasting friend of Masereel.

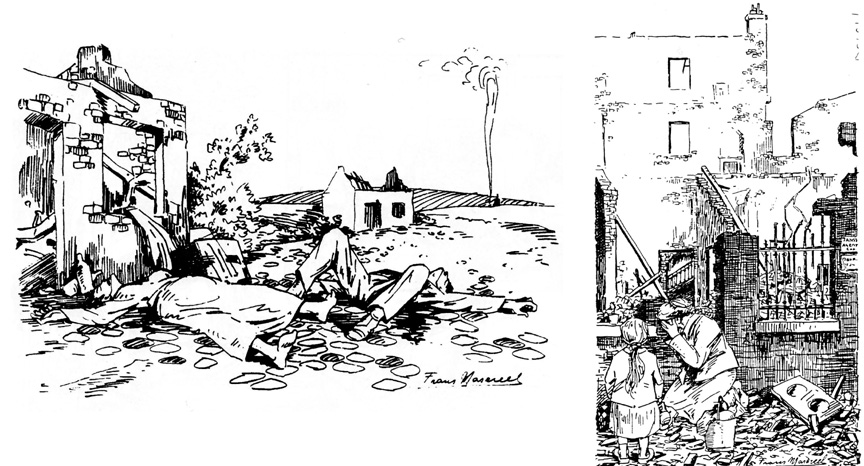

The quality of Masereel’s early anti-war drawings from 1914 – 15 are displayed in his illustrations to La Grand Guerre Par Les Artistes by G. Geffroy and La Belgigue Envahie by Roland De Marés that depict Belgium refugees during the war with extreme emotion in the expressions of the characters.

Masereel was introduced to the woodcut through Quatreboeuf, a dealer in art supplies and friend of Bernard Naudin, who was noted as a printmaker and book illustrator. Masereel was unaware of the use of the woodcut by German Expressionists and the revival of the craft in France displayed in the work of artists like Félix Vallotton. He was immediately fascinated with this medium that he privately taught himself in the subsequent months. When World War I broke out he moved to Geneva where Guilbeaux had retired. Through his friendship with Guilbeaux, Masereel met Romain Rolland, Stefan Zweig, and a group of pacifists who shared his beliefs. He became close friends with Rolland, who described Masereel at that time:

He’s an athletic fellow, with a black beard and glasses; he is reserved, like a Spaniard, and one could take him for one. He is in fact, Flemish, from Ghent, and he is twenty-eight, but he looks at least thirty-five. He is very likeable, and certainly very kind, incapable of the slightest pettiness. The present spectacle is incomprehensible to him, and fills him with horror (18).

Masereel joined this group and worked as a translator for the International Red Cross.

He contributed early woodcuts to the periodicals Demain, 1916 and Les Tablettes, 1916 – 1918;

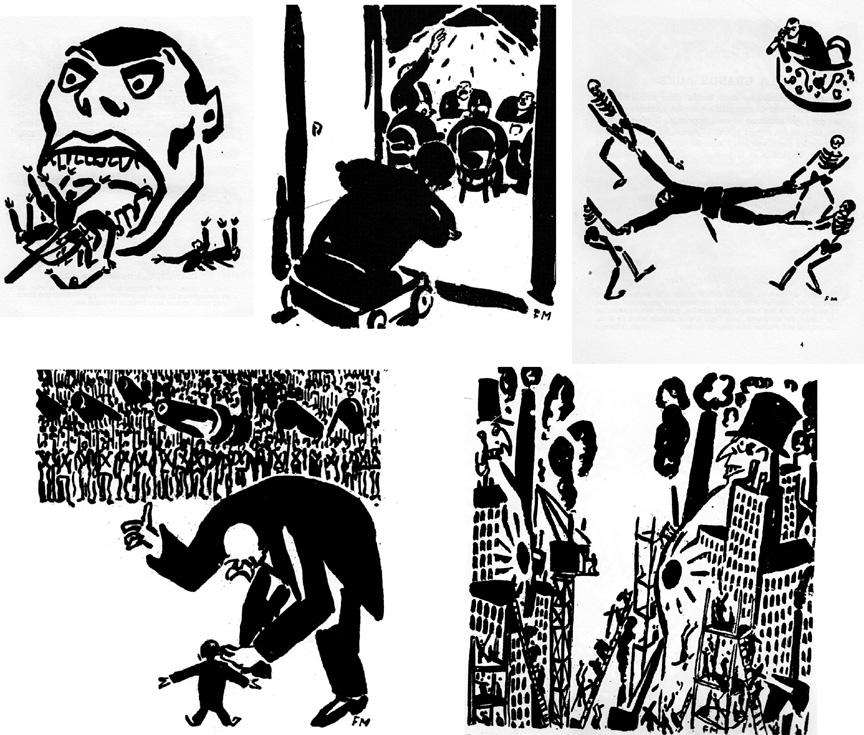

and drawings to the newspaper La Feuille, 1917 – 1920, where he mastered a method using brush and ink to create a single anti-war drawing related to the news of the day while meeting a daily publication deadline.

He learned to incorporate exaggerated gestures and emotions in these drawings, which is a device used in cartoons that Masereel would fully develop during his time at La Feuille and master in his woodcut novels, early examples of today’s wordless graphic novel. A selection of forty-eight drawings from this extensive collection was published in 1920 under the title Politische Zeichnungen. During the three years that he worked at La Feuille, he created over 1,400 drawings. Over this period of time, his focus on the war changed in his woodcuts and drawings; and “…in them he would typically juxtapose the pronouncements of a politician or industrialist with a scene of battlefield carnage, and in doing so showed the vast gulf between the official rhetoric of the war and the reality” (Willett, 111).

Masereel continued to work with the woodcut, became more assured of his skill, and published fifty-seven woodcuts in Quinze Poèmes by Emile Verhaeren in 1917. An examination of these early efforts reveals a traditional approach in the medium. His characters are stiff and the engraving seems restrained. Many of these early woodcuts have none of the defining elements of Masereel’s recognized style. It is the brush and ink drawings that he created for La Feuille that released him from this rigid style. All artists try on different hats during their development as artists. It is to Masereel’s credit that he chose to abandon a traditional style for one that was free flowing and visually inspiring, one that supported his calling as an artist whose “…primary passion and commitment was humankind itself: a boundless solidarity with his fellow-creatures” (Engel, 9).

It was during this transformation that Masereel found an inimitable style that he would extend into a substantial body of work, which began with his first wordless book of ten woodcuts in Debout Les morts (Arise Ye Dead). Like his work in La Feuille, in this folio he displayed the horrors of World War I not only in the trenches but also in those experiences of women and children in a mix of bizarre fantasy and surreal displays. He does not hesitate to portray the gruesomeness of war on the title page, with a half page woodcut of men without limbs, which is carried through to a print with more soldiers cut in half or crawling on the ground as their entrails spill out of their stomachs. His use of Christian symbolism appears on the first full page with an image of the crucifixion, commonly symbolizing suffering and salvation. The suffering is presented in the foreground with a man, his hands bound, showing an expression of pain while the symbol of salvation is in the distant background, behind the man who is unable to see or reach for any promised redemption.

In three other scenes of death in the trenches, solders rot in barbwire fences that have wrapped around their bodies and appear like wooden posts. Other prints display soldiers gouged on sharpened wooden stakes or screaming in terror as they are burned alive in a human bonfire. One can only imagine the sounds of wailing and unimaginable pain depicted in these woodcuts. In two other prints, an anchor, a symbol of hope, holds a mother down in a rising tide rather than offering salvation. She clutches the hand of her drowned child at her side, desperately raises her other hand in supplication, and bends her head back as far as possible to keep from drowning. Her dress has shamelessly risen above her thighs as she impassively prepares herself for death. In a surrealistic and cartoon-like display, Masreel presents two headless soldiers carrying the heads of two opposing soldiers on a stretcher as they march across a stark field. In the final selection of prints, a skeleton storms out of a crypt as a industrialist races away from the grave and a woman is assaulted by a skeleton — both using personifications of Death that Masereel used extensively in La Feuille and in many of his other works. His use of white space, in contrast to the strong black ink in his woodcuts present enduring images that shake up one’s visual sensibilities like no other artist.

In the same year, he published another book of prints, Les Morts Parlent (The Dead Speak, 1917) that dramatically incorporated this personification of Death. In addition, Masereel illustrated nine books predominantly in woodcuts from 1918 – 1920 with his disturbing focus on death and the wreckage of war.

The end of the World War I left little time for celebration before the rise of Fascism. Masereel once again used his graphic skills to record the atrocities of another world war in poignant wordless novels like Danse Macabre (1941); Juin 40 (1942); Destins 1939−1940−1941−1942 (1943); La Terre sous le signe de saturne (1944); La Colère (1946); Remember! (1946); and numerous book illustrations by various authors on the slaughters and genocide from 1935 – 46.

In his [Masereel] late work, especially that during World War II, you will find virtually every contested political and moral theme any writer or thinker has identified about the war, its aim, its morality (Bruckner, 57).

The threat of nuclear war against the backdrop of a rising technological and materialistic zeal lead Masereel to examine the predictable destruction of the human race. He explored our return to a more compassionate and primitive lifestyle in wordless books from 1949 ‑1966 including Ecce Homo (1949); Notre Temps (1952); Die Apokalypse unserer Zeit (1953); and Pour quio? (1954). Ultimately, his stunning woodcut illustrations to Johannes R. Becher lyrical work Vom Verfall zum Triumph (From Decay to Triumph, 1961) is perhaps Masereel’s closing message of hope to our warring world, presented in a highly symbolic style and packed with iconic language that begs interpretation.

Bibliography

Avermaete, Roger. Frans Masereel. London: Thames and Hudson, 1977. Print.

Bruckner, D J. R, Seymour Chwast, and Steven Heller. Art against War: 400 Years of Protest in Art. New York: Abbeville Press, 1984. Print.

Engel, Walter. “The World of Frans Masereel.” Tribute: Frans Masereel, an Exhibition of Paintings, Watercolours, and Graphics, September 13-October 25, 1981, Art Gallery of Windsor. Windsor, Ont., Canada: The Gallery, 1981. 9 – 86. Print.

Willett, Perry. “The Cutting Edge of German Expressionism: The Woodcut Novel of Frans Masereel and Its Influences.” A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism. Ed. Neil H. Donahue. Rochester, N.Y: Camden House, 2005. 111 – 134. Print.

Figures

Fig 1. Frans Masereel. Illustration for La Grand Guerre Par Les Artistes by G. Geffroy, 1914 – 1915.

Fig 2. Frans Masereel. Illustration for La Belgigue Envahie by Roland De Marés, 1915.

Fig 3. Frans Masereel. Demain, 1916.

Fig 4. Frans Masereel. Les Tablettes, August, 1917.

Fig 5. Frans Masereel. La Feuille, May 28, 1918.

Fig 6. Frans Masereel. La Feuille, February 25, 1918.

Fig 7. Frans Masereel. La Feuille, June 20, 1918.

Fig 8. Frans Masereel. La Feuille, January 27, 1919.

Fig 9. Frans Masereel. La Feuille, October 21, 1919.

David A. Beronä is a historian of the woodcut novel and wordless comics. He is the author of Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels (2008) — with editions in French and Korean, a winner at the New York Book Show, and a Harvey Awards nominee. He has published and presented papers widely on these topics with essays in Critical Approaches to Comics: Theory and Methods (2011) and The Language of Comics: Word and Image (2001). He selected and edited Alastair Drawings and Illustrations (2011) and Eric Gill’s Masterpieces of Wood Engraving (2013). He is a member of the visiting faculty at the Center for Cartoon Studies and the Dean of the Library and Academic Support Services at Plymouth State University, New Hampshire.

David A. Beronä is a historian of the woodcut novel and wordless comics. He is the author of Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels (2008) — with editions in French and Korean, a winner at the New York Book Show, and a Harvey Awards nominee. He has published and presented papers widely on these topics with essays in Critical Approaches to Comics: Theory and Methods (2011) and The Language of Comics: Word and Image (2001). He selected and edited Alastair Drawings and Illustrations (2011) and Eric Gill’s Masterpieces of Wood Engraving (2013). He is a member of the visiting faculty at the Center for Cartoon Studies and the Dean of the Library and Academic Support Services at Plymouth State University, New Hampshire.

You must be logged in to post a comment.