An Interview with Howard P. Lovecraft

(as uncovered by Nick Mamatas)

I spent about eighteen months in Brattleboro, Vermont in the middle of the last decade. I learned a lot of things, mostly about myself. For one thing: Brattleboro is a great small town. For another: I dislike small towns, even the ones with more bookstores than traffic lights. But I did love the bookstores, especially a used paperback house called Baskets Bookstore/Paperback Palace. Huge horror and romance sections — Sherwood, the owner, laughed when I christened the romance section “The Pink Bomb.”

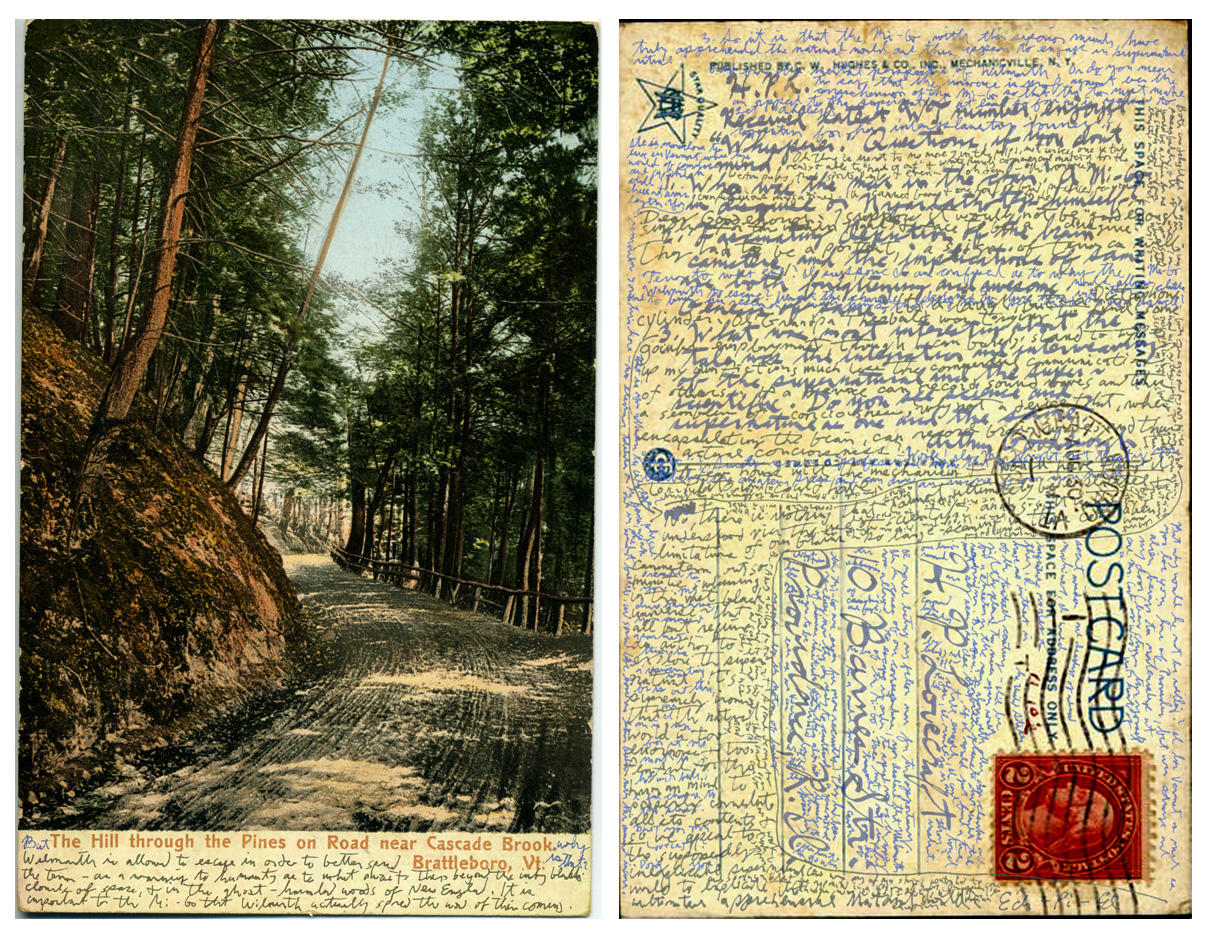

Most paperbacks were cheap enough to be purchasable by the basket, which was perfect for the long winter nights, but some of the items for sale were quite a bit rarer. One day he handed me a postcard sent between H.P. Lovecraft and Arthur H. Goodenough, an amateur press enthusiast living near Brattleboro. Goodenough isn’t talked about much today, but Brattleboro is still full of Goodenough — there’s a road named for the family (or was the family named for the road?), a trash removal firm, you name it.

Lovecraft was acquainted with Goodenough, and Lovecraft’s visits to Goodenough in Vermont in 1927 and 1928 are the basis of his wonderful novelette “The Whisperer in Darkness.” After the story was published in Weird Tales, Goodenough sent Lovecraft a congratulatory card, and also asked the author a couple of questions. Rather than responding with a card or letter of his own, Lovecraft wrote the answers in a tiny hand and then apparently gave the card to Vrest Orton — a bookman and eventual founder of The Vermont County Store — who returned the card to Goodenough personally during a trip to the Green Mountain State. Then Goodenough sent the card back to Lovecraft again, with follow-up questions written in a nearly microscopic hand. I suppose he knew the local postmaster, and was able to get the card back into the mail system without a problem. Amazingly, Lovecraft managed to fit the answers to the questions on the postcard in an even smaller hand. Sherwood told me that he’d guessed that Lovecraft used a magnifying glass and a sewing needle dipped in ink. Here’s an odd thing; Sherwood had found the postcard at an estate sale. It had been protected from the elements because it had been used as a bookmark in a 1935 number of The Revelator, and that number was a special issue dedicated to the “gothic tales” of Isak Dinesen.

I bought the card and kept it with me for years — I moved to Boston, and then to California. Only recently have I been able to spare the time to closely examine and transcribe the postcard. It took a few weeks. Lovecraft’s handwriting was difficult to read in the best of times, as I learned in 2007 when writer Brian Evenson took me and my friend Geoffrey Goodwin to the library at Brown University to check out some of Lovecraft’s papers. If anything, Goodenough’s penmanship is even worse, especially in the last unanswered round of questions. There are a few ink splatters on the postcard as well, but only one seems purposeful, as I make note of below. I took the card to work and abused my photocopy and scanner privileges to blow up sections of the card, then turn them into a series of PDFs. I then zoomed in on the PDFs as much as I could, to turn the tiny letters into great abstract shapes, to better see what we would call “kerning” if the text had been typset. To decipher this postcard, I not only had to read between the lines, as it were, but I had to make sure I was properly reading between the letters.

My friend Raphael is Google’s resident font expert and I showed him the PDFs. Raph’s PhD thesis is on imaging and halftoning over at the University of California at Berkeley, and he was able to use his research to cobble together a program to “draw” my blow-ups in a way that made the letters more legible. It was still a game of refrigerator poetry for a while, as the letters, words, and sentences the computer spit out barely made sense. Only after reading S. T. Joshi’s two-volume biography of Lovecraft was I finally confident in my deciphering of the card.

We already know a lot of Lovecraft’s life and beliefs, which is a great part of why all of the many short stories in which Lovecraft is a character and the theme of the story is, “Everything Lovecraft wrote about was real! Real!” are so tedious. He was a philosophical materialist and a metaphysical skeptic, so of course there will be no secret correspondence, no occult messages, in the transcription below. But the postcard is interesting, and illuminating, and strange, in its own way.

—Nick Mamatas

***

HPL—

Received latest WT number, enjoyed “Whisperer.” Questions, if you don’t mind.

1. Who was the man in the chair? A Mi-Go in disguise or Nyarlathotep himself?

Dear Goodenough. I suppose it would not be “good enough” simply for the waxen hands and face to be a disguise. They had to be a portent, a sign of a terror as well.

Terror to what end? I suppose I am confused as to why the Mi-Go would allow Wilmarth to escape? Wasn’t the charade designed to lure him in to their clutches, and to bring his researches with him so that they might seize and destroy them as well?

Wilmarth is allowed to escape in order to better spread the terror — as a warning to humanity as to what awaits them beyond the inky black clouds of space, & in the ghost-haunted woods of New England. It is important to the Mi-Go that Wilmarth actually spread the word of their coming.

But why is that?

[Lovecraft doesn’t respond. Presumably, the card was not sent back to him as the third “layer” of questions go entirely unanswered.]

2. Fascinating depiction of the brain canisters, and the implications of same are both frightening and awesome. Genesis of same?

It’s a laugh, but — a Dictaphone cylinder. Ol’ Grandpa Theobald was trying to find some gainful employment, though I can barely stand to type up my own fictions much less the commercial communications of others. If a device can record sound waves and thus a semblence of consciousness, why not a device that, when encapsulating the brain, can record brain waves and thus actual consciousness? A few hours with the mechanism & I would have flung it to Pluto if I could have.

Work! Is Mr. Wright not treating you “right”? Surely you’re a “professional” now that you’ve left beind the amateur press and can draw an income from your work.

Oh, there is next to no money in the pulps, not unless one is truly ready & able to “hack it out” and write purely commercial material for the Western pulps, the sports pulps, & even — oh dear — the romance & confessions magazines. It’s canned beans & one loaf of bread, pre-sliced, per week for me.

It is marvelous to live in Vermont, where the world of commerce and capital is still held at arm’s length. You remember your time here — no electrical utilities on the farm, physical work out in the verdant fields, and social life based on fellow-feeling rather than annual income. What is your attraction to city life?

[Again, no answer. This question reads almost as a dig. Surely, Goodenough knew that Lovecraft loathed cities, with the exception of Providence, Rhode Island. Lovecraft’s 1927 visit to Vermont came on the heels of his return to New England after escaping the racially diverse and economically cratered neighborhood of Red Hook, in Brooklyn NY. It is hard to imagine Lovecraft not confiding his fears and frustrations with the urban life in Goodenough. Perhaps Goodenough was more progressive than Lovecraft, and wanted to needle him a bit. Incidentally, I’ve been to Red Hook many times, as my father works there as a longshoreman. By my sights gentrification is just another form of ruination, rather than its negation, but Lovecraft would fit right in these days — he was a cult writer who dressed funny and adopted many odd affectations, after all.]

3. What was most interesting about the tale was the integration and interweaving of the supernatural and the superscientific. Do you see science and supernature as one and the same?

No, there is nothing that cannot be ultimately explicated & understood via the use of scientific analysis. It is the limitations of our brains — so large-seeming in those cozy alien cannisters, but so minute swimming in this vast black universe — that all but require an author to explore the supernatural. It’s supremely ironic that the natural world is too enormous and too fearful for the human mind to properly correlate all its contents & so we appeal to the supposedly inexplicable supernatural world to explicate the ultimately apprehendable natural world.

So is it that the Mi-Go, with their superior minds, have truly apprehended the natural world and thus appear to engage in supernatural ritual only from the mental perspective of Wilmarth? Or do you mean to say that the universe is proof against even the comprehension of the Mi-Go so that they too must make an appeal to the supernatural, at least so far as is required to get Akeley’s cooperation for his interplanetary journey?

Both are delightful possibilities, & it would be a shame for me to simply record my own thoughts on the subject, as if your own were supernumerary. Also, I am surely challenging both your eyes and my own hand with my itsy-bitsy microminiature script as it stands. The Mi-Go are greater beings than we, but then again, who ain’t? But among the bestiary of Yog-Sothory they aren’t nearly the greatest or most profound of beings. I suppose the Mi-Go are rather like us. As we might pin butterflies to a mounting board or attempt communication with a bestial tribe of [here the work is redacted by a blot of ink spilled on to the card, and the coloring suggests that it is from Goodenough’s pen, not Lovecraft’s] from darkest Africa, they seek to learn about us through a variety of means.

But Akeley, a willing participant? A proud Vermonter acquiescing to having his skull sawed open and its insides scooped out in order to fill a can of beans? I never reread my own work, though I suppose that were any of my stories contracted to be reprinted in a volume of tales (Oh green and somnambulant Cthulhu, were it so!) I might, but in this case I’ll make an exception.

But why would he not be willing? I love Vermont as much as you love your home of Providence, but were strange and alien beings to materialize at my door (being stranger than yourself and Mr. Cook anyway) with hints of a secret wisdom and displays of advanced machinery, I would give my all to ingratiate myself to them. I have no interest in the United States of the twentieth century — I’d be rightly pleased to never again wait for a streetcar in the rain along with the other dour clerks and workingmen. But space? Forbidden planets that under the night sky seem so close that, if I could just find a tree tall enough, I could touch them? Yes, I would go in a moment. I would betray my fellow man for the opportunity.

In the course of our correspondence, you declared that Wilmarth was allowed to escape in order to spread word of the coming of the Mi-Go. Does that not imply that the Mi-Go are eager for more recruits? They had been recluses; now they are ready to cultivate a generation of human initiates into their alien rites. Surely, we are to be tantalized by this possibility, even as we are repulsed by the notion of having our brains removed and canned like peaches by beings who appear to be the offspring of crustaceans and fungi, to be transported to a world far from the green hills of Earth.

What is there here for men like us, Howard? Won’t you take the opportunity to go when it is presented to you? My dreary old farmhouse, your cramped apartments — there is a universe waiting for us out there, and I am in a rage for it. My mouth is hot with bile; I feel chained to this planet. Don’t you, Mr. Lovecraft? Don’t you?

[Of course, there is no answer, and not a spare millimeter left on the card for one.]

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including the Lovecraftian works Move Under Ground and, with Brian Keene, The Damned Highway, as well as stories in Lovecraft Unbound, Future Lovecraft, and Black Wings II.

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including the Lovecraftian works Move Under Ground and, with Brian Keene, The Damned Highway, as well as stories in Lovecraft Unbound, Future Lovecraft, and Black Wings II.

You must be logged in to post a comment.