Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City begins in medias res (“And so when I began to go on evening walks last fall…”), and it explores what it means to be dropped into the maelstrom of history. Open City is a novel about walking, about cities, about life in this strange century following the turbulent bloodiness of the 20th. It is a novel about what it means to make sense of our own personal place in history, and in the stories of our own tribes, and in the stories of our planet. Many of these stories, the triumphant ones especially, we project ourselves into in order to feel heroic. Many of these stories, the horrific ones especially, we never asked to be a part of and we spend our lives distancing ourselves from those. At its best, Open City is a novel about all the complex and contradictory ways we make sense of ourselves as historical subjects.

I’ve been a New York City tour guide for about ten years now, and I’ve taught many courses on the literature and history of New York. The City is a great teacher of history, full of endless fascinations and revelations and a staggering complexity that can only be grasped through partial comprehensions and incomplete understandings. To deal with New York one must accept above all that it will always bewilder the completist.

There are layers to the city. Julius, the narrator of Open City, a young German-Nigerian psychiatrist, stands at the World Trade Center site five years after September 11, 2001 contemplating the Syrian and Lebanese communities that were pushed out to make way for the twin towers. “And before that?” he asks, “What Lenape paths lay buried beneath the rubble? The site was a palimpsest, as was all the city, written, erased, rewritten…Generations rushed through the eye of the needle, and I, one of the still legible crowd, entered the subway. I wanted to find the line that connected me to my own part in these stories.”

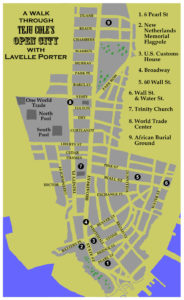

What follows is a walking tour through Teju Cole’s Open City. It is designed as a walkable two-hour tour that covers a portion of Lower Manhattan. It necessarily excludes Morningside Heights (where Julius lives), Central Park South (where his mentor Dr. Saito lives), and other locations he visits like Chinatown and Harlem and Fort Tryon. And, naturally, it doesn’t cover Nigeria, where Julius grows up, or Belgium where he goes on vacation. But it does cover one of the most important locales in the novel, the birthplace of the metropolis, Lower Manhattan. This tour is an incomplete story, as stories can only be. (One story that I omit by focusing on the historical parts of Open City is the revelation that Julius sexually assaulted someone in his past, a detail that this #MeToo era reminds me I should not entirely leave out, spoiler alerts be damned.)

Any tour of New York must begin in the middle of things. And yet the historian’s impulse is to find the point of origin from which to start a coherent narrative connecting us to what we see and experience. If a story is going to be told, then you have to pick a place and start telling. Though this tour was inspired by Open City, one need not have read the novel to appreciate these historic sites.

I taught Open City in my literature classes in the fall of 2016. We met up for a walk through Lower Manhattan on a rainy, cold Friday in October. When we walked toward the back of 17 State Street, I was shocked to find that the bust of Herman Melville that had been there for years was gone. Immediately I thought of another great piece of New York literature, Colson Whitehead’s Colossus of New York, wherein he writes that one of the essential feelings of this city is the sense of loss when you visit a place that has suddenly disappeared on you. As he puts it, this is a city where “we can never make proper good-byes.” I still don’t know what happened to the bust of Melville. Being a New York City tour guide means constantly revising your narrative to accomodate new realities.

In Open City, the first mention of Melville comes after Julius rides the subway down to Wall Street and walks to Trinity Church on Broadway, but finds that the gates of the church are closed that day.

“About two hundred years later, when a young man from the Fort Orange area came down the Hudson and settled in Manhattan, he decided he would write his magnum opus on an albino Leviathan. The author, a sometime parishioner of Trinity Church, called his book The Whale; the subtitle, Moby-Dick, was added only after the first publication. This same Trinity Church had now left me out in the brisk marine air and given me no place in which to pray. There were chains on all the gates, and I could find neither a way into the building nor anyone to help me. So, lulled by sea air, I decided to find my way to the edge of the island from there. It would be good, I thought, to stand for a while on the waterline.”

In fact, Melville, the young man from the Fort Orange area (later Albany, NY) was born in Lower Manhattan, in a house on 6 Pearl Street in 1819. The missing bust I was looking for had been installed there to mark the site of his birthplace.

I recognized that passage from Open City, with its reference to standing at the waterline, as an allusion to the first chapter of Moby Dick, or the Whale, which actually begins in Melville’s hometown. His description of Lower Manhattan in the middle of the 1800s is a good snapshot of the metropolis as it grew into a vibrant port city.

“There now is your insular city of the Manhattoes, belted round by wharves as Indian isles by coral reefs — commerce surrounds it with her surf. Right and left, the streets take you waterward. Its extreme down-town is the battery, where that noble mole is washed by waves, and cooled by breezes, which a few hours previous were out of sight of land. Look at the crowds of water-gazers there…Circumnambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip, and from thence, by Whitehall northward. What do you see? — Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries.”

New Netherlands Memorial Flagpole (near the Intersection of State Street and Battery Place)

A great site to make sense of how that “insular city of the Manhattoes” went from Native American land, to Dutch outpost, to British city, to American metropolis, is this flagpole with its granite base that contains a bas-relief of a map showing Manhattan as it looked in the mid-1600s. The flagpole was a gift from the Netherlands to the city of New York in 1926 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the founding of New Amsterdam.

In Open City we get some case history about one of Julius’s patients, a woman only identified by the initial V. She is a Native American and an academic historian who studies the history of Native Americans in New York. V. is going through a depressive episode and is deeply affected by the history of brutality and genocide that she is writing about.

The flagpole has four sides. On the front is the map of Lower Manhattan, on two sides there is a narrative of the founding of New Amsterdam (one side in Dutch, the other in English) and on the back is a depiction of trade between a Dutch colonist and a Native American. Legend has it that in 1626 Peter Minuit, director-general of Dutch New Amsterdam, negotiated with the Lenape Indians for the purchase of the island of Manhattan for $24 worth of trinkets. There is no actual record of this transaction. What we know about this sale mostly comes from a letter sent back to Holland in 1626. The image on the pole shows the friendly relations of trade between the Dutch and Native Americans. But a visit to the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian just across the street inside of the US Custom House will let you know that this is an incomplete story to say the least. The full story is bloodier than this depiction. In Open City, V. struggles to tell that story of genocide, even as it takes an emotional toll on her own well-being.

“I went down Broadway, past the Old Customs House, and down to Battery Park…The Customs House faced Bowling Green, which had been used in the seventeenth century for the executions of paupers and slaves.”

For New York historians, what Julius calls the “old” Custom House is actually the “new” Custom House. This 1907 Beaux Arts building designed by architect Cass Gilbert, is the third site of the customs service in the city. Previously it was in the building that is now Federal Hall on Wall Street from 1842 to 1862, and then from 1862 to 1907 in the Merchants Exchange building down the block at 55 Wall Street. In the 1890s the U.S. Treasury department bought the land near Bowling Green for Cass Gilbert’s majestic building. The interior rotunda ceiling is covered with murals by the artist Reginald Marsh. In front of the building are four sculptures, Four Continents, by Daniel Chester French. Asia and Africa are on the outsides with both their eyes closed, representing empires of the past that have yet to reawaken. Europe and the Americas are in the middle. The design of the sculptures and their layout are instructive in their Orientalism and Eurocentrism. The Asia sculpture depicts servitude and bondage, the Africa sculpture naps, naked with her head drooped down. Europe is on the throne representing the monarchies of old Europe, and the Americas, the most dynamic statue in the group lurches forward into the future. Four Continents is a visual representation of the ideology of American exceptionalism, an artist writing the nation into the history of the world’s great trading empires. Behind the sculptures, inside of the building, the exhibits of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian help to contextualize the human cost of these global aspirations.

And across from the Custom House is Bowling Green Park, the oldest public park in the city, dating back to 1733. As Julius mentions it was one of several sites used for executions (see Jill Lepore’s New York Burning for a glimpse into the barbarity of capital punishments in colonial New York.) It was also the site of a loyalist statute of King George III put up in 1771, a statue toppled five years later by rowdy colonists who had just heard the Declaration of Independence.

Standing just north of Bowling Green Park on a clear day you can see up Broadway into Midtown with the Art Deco top of the Chrysler Building off in the distance. Here is one of those former Lenape paths that Julius asked about, the most famous one, the longest Avenue in the city. Its name, which originated from the Dutch “Brede Weg” is now synonymous with the City and its culture industries. Broadway begins here and stretches not only the 13.5 miles of Manhattan island, but then continues north and links to US‑9 heading toward the state capital in Albany.

On one of his impromptu adventures, Julius takes the 2 train downtown and decides to get off at Wall Street. He takes a subway exit that empties out into the indoor atrium of the Deutsche Bank building at 60 Wall Street.

“I took the escalator up, and as I came out onto the mezzanine level, I saw the ceiling – high, white, and consisting of a series of interconnected vaults – slowly reveal itself as though it were a retractable dome in the act of closing. It was a station I had never been in before, and I was surprised that it was so elaborate because I had expected that all stations in lower Manhattan would be mean and perfunctory, that they would consist only of tiled tunnels and narrow exits…My original impression of the grandeur of the space, though not of its size, quickly changed as I walked through the hall. The columns could have been wrought from recycled plastic chairs, and the ceiling seemed to have been carefully constructed out of white Lego blocks. This feeling of being in a large-scale model was only increased by the lonely palm trees in their pots, and by the few groups of people I now saw seated under the nave aisle to the right…The hall was sparse, and because it was enclosed, full of the echoes of the few voices present.”

Like so many things in this novel, Deutsche Bank also has a longer story connecting it to September 11. 60 Wall Street was built in 1989 as the headquarters of JP Morgan and Company (which merged with Chase) but later acquired by Deutsche Bank early in 2001. On 9/11/01 Deutsche Bank was still operating in their previous building located near the WTC site, a building which was severely damaged in the collapse of the towers. In the aftermath, they relocated their operations into this new building. The damaged building was kept intact due to concerns about toxic contamination if it were leveled. There were also human remains still being found at the site, so the building was not allowed to be dismantled until it could be thoroughly searched. In 2007 two firefighters were killed in a fire at the building. It was finally dismantled in January 2011.

Later in the narrative, when Julius comes back to the Financial District to visit his accountant (and forgets his ATM password), he mentions the relationship between Wall Street and slavery. The eastern end of Wall Street at Water Street was the sight of the former slave market. In 2014 a sign was placed there to commemorate the location. At the same intersection, the New York Stock Exchange was founded under a buttonwood tree in 1792. There’s an intricate relationship between those two entities. Wall Street was a literal wall built by African slave labor. The wall is now represented by a series of wooden blocks embedded into the surface of the street to show where it once stood. Figuratively, “Wall Street” was built by the profits of a slave economy, a fact that the new sign acknowledges. And a few blocks north is the African Burial Ground, a testament to the city’s selective memory about its history.

Trinity Church (Wall Street and Broadway)

The congregation dates back to the 1690s when it was started by the Anglican Church. It has gone through three buildings, the first burned down in the Great Fire of 1776 during the Revolutionary War, the second dismantled after severe roof damage from snowstorms during the winter of 1838 – 39. Its current building is an 1846 Gothic brownstone beauty designed by architect Richard Upjohn, topped off with a 281-foot spire that was the tallest point in New York until the completion of the New York World Building in 1890.

In the novel Julius goes to visit the grave of Alexander Hamilton. It was always a popular site, but has grown even more so since Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical conquered Broadway in 2016. It was here that Hamilton was buried after he died from injuries suffered in that infamous duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. His wife Eliza is buried in front of him, and his son, Philip, who died in a duel in 1801, is buried next to them. Every day that the churchyard is open a steady stream of tourists comes by to snap pictures next to the obelisk monument. So many of them have come that they have now bypassed the concrete footpaths that circle through the cemetery to the Hamilton site, and have beaten a dirt path through the grass directly to it.

209 Broadway, and the World Trade Center

From Broadway, next to St. Paul’s chapel is a view of the One World Trade Center tower, 1,776 feet tall at the tip of its spire, which opened in 2015. Next to it is the weird rib cage structure of the rebuilt Path station, recently opened in 2016. It was still “Ground Zero” when Julius walks to the site in late 2006. “The place had become a metonym of disaster: I remembered a tourist who once asked me how he could get to 9 ⁄ 11: not the site of the events of 9 ⁄ 11 but to 9 ⁄ 11 itself, the date petrified into broken stones.”

You can now visit the massive waterfalls flowing down into the two footprints where the towers once stood, and visit the 9 ⁄ 11 memorial museum. It’s a funny thing, this memorializing. The mood there is…strange. It’s a somber place, and yet with the passage of time it has developed the indifferent ambience of a shopping mall. Recently some young tourists were scolded for taking sexy selfies next to the pools where behind them sit plaques engraved with the names of the dead. Many of my own students were toddlers on that day. For them 9/11/01 is not a memory, but a date in history that they learn about in school and make meaning of through stories, and through monuments like this.

African Burial Ground (Duane Street between Broadway and Elk)

As Julius heads toward the African Burial Ground he notes “the massive Long Lines building on Church Street. It was a windowless tower, a giant concrete slab rising into the sky.” In that building were the switchboards of AT&T, and it now houses some of the apparatus for its Internet operations, a symbol of the always-on, networked, digital lives we now lead, even as the hardware that enables this life mostly remains opaque and concealed out of sight.

The official address of the African Burial Ground is 290 Broadway, which houses the visitor’s center inside of the Ted Weiss Federal Building. The outdoor monument is actually around the corner on Duane Street, east of Broadway.

The first enslaved Africans were brought to Manhattan by the Dutch in 1626. Slave labor was instrumental in the building of New Amsterdam and continued through the building of British colonial New York. The enslaved worked in a variety of fields, including as farm labor, dockworkers, domestic servants, and even as skilled artisans and craftsmen.

Africans were not allowed to be buried in the city’s church cemeteries. From the 1690s to the 1790s, the “Negros Burial Ground” served as the final resting place for some 20,000 enslaved and free blacks in New York. In 1799 New York adopted a policy of gradual abolition to phase out the institution of slavery. July 4, 1827 is Emancipation Day in New York, as slavery was officially outlawed statewide. The burial ground closed in the 1790s and the area was divided up and sold to developers. Over the years, it was built over without any regard for the bodies underground.

In 1991 the site came back in a big way. In Freudian terms, you might say this was the return of the repressed. Construction crews began excavating the site for a federal office building, and soon their digging brought up human remains. After protests from activists, eventually the construction stopped and 419 bodies were unearthed. The excavated remains were taken to laboratories at Howard University in Washington, D.C. where forensic anthropologists could study the bodies to determine genders, ages, and probable causes of death. The bodies were brought back and reinterred in a ceremony in 2006. The museum and visitor’s center opened in 2010.

The memorial design is titled “Door of Return,” based on the “Door of No Return,” the name given to passageways in slave castles on the coast of West Africa where the enslaved were transported to the Americas. The water cascading into the inside of the memorial, collecting in pools on each side of the staircase down into the main chamber, symbolizes the Atlantic Ocean and the Middle Passage. The site is adorned with Sankofa symbols. The principle of Sankofa is to “Learn from the Past to Prepare for the Future.” And down on the floor of the main chamber are the approximate ages and probable causes of death for the 419 bodies exhumed from the site.

While standing at Ground Zero Julius says, “The site was a palimpsest, as was all the city, written, erased, rewritten,” but it is here at the African Burial Ground, a site once hidden and now made visible again with a memorial, which was only built after protest and agitation, that one finds the most potent symbol of the palimpsest, and the City’s complicated relationship with its past.

Postscript

I finished this piece over two years after my 2016 class. Of course, that fall was also the season of a most unfortunate presidential election. On Wall Street the air is poisoned by that name in gaudy gold lettering on the building at 40 Wall Street. In the months before the election I avoided and redirected the narrative away from that name as best I could. I haven’t led many public tours since then, and given this climate I’m not crazy about doing so. I can’t be “objective” about this site, and I don’t feel like making nice with dudes showing up in those dumb, cheap red hats. (I’ve seen a few of them sprinkled around touristy areas in the city, now by the Charging Bull, now on the Brooklyn Bridge, now in Times Square.)

At the African Burial Ground, Julius thinks of the enslaved Africans who lived and died in the early colonies. They were not just slaves, but people with hopes and dreams and desires who led quotidian daily lives. We go on living in and around atrocity, and I’m afraid this administration will bring more atrocities that many of us will not survive. The African Burial Ground is there as a testament to resistance and persistence, on the part of the enslaved, and on the part of those who demanded that the city bear witness to their suffering. There’s no better place to remember why we fight.

Bibliography

Cole, Teju. Open City. New York: Random House, 2011.

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Guide to New York City Landmarks. 4th edition. Hoboken: Wiley, 2008.

Kamil, Seth and Eric Wakin. The Big Onion Guide to New York City. New York: NYU Press, 2002.

Lepore, Jill. New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

Whitehead, Colson. The Colossus of New York. New York: Random House, 2003.

Wolfe, Gerard R. New York: 15 Walking Tours, An Architectural Guide to the Metropolis. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Download a pdf version of the walking tour map

Lavelle Porter is an Assistant Professor of English at New York City College of Technology, CUNY. His writing has appeared in venues such as The New Inquiry, Poetry Foundation, JSTOR Daily, Callaloo, and Warscapes. He is a regular contributor for Black Perspectives the blog of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS). His first book The Blackademic Life: Academic Fiction, Higher Education, and the Black Intellectual is forthcoming from Northwestern University Press.

Lavelle Porter is an Assistant Professor of English at New York City College of Technology, CUNY. His writing has appeared in venues such as The New Inquiry, Poetry Foundation, JSTOR Daily, Callaloo, and Warscapes. He is a regular contributor for Black Perspectives the blog of the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS). His first book The Blackademic Life: Academic Fiction, Higher Education, and the Black Intellectual is forthcoming from Northwestern University Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.