THE REVELATOR was a proud and earlier proponent of The Wizard of Oz comics, running the entire L. Frank Baum series from its inception as a national Sunday feature in 1904 through to the final daily strips starring Toto in 1917. Indeed THE REVELATOR, beneficiary of a hitherto unheard of licensing arrangement with Baum, carried the strip as an exclusive for a decade. It is during THE REVELATOR years from 1907 to 1917 that The Wizard of Oz comic strip innovated the characteristics that would influence later comics luminaries such as Milton Caniff, Chester Gould, and Charles Schultz.

A series of strange newspaper reports appeared in 1904, culminating in a “Proclamation Extraordinary” that read:

From the Land of Oz to the United States. Here they come! The Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, Jack Pumpkinhead, the Woggle-Bug, the animated Sawhorse, and the Gump! They are on their first vacation away from the Emerald City and the Land of Oz. They want to romp with the children of the United States.

It was true! Dorothy and a cohort of her remarkable friends from Oz had escaped the confines of the book and landed smack-dab in the Sunday comics’ section of the nation’s newspapers. The comic followed the success of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900 and occurred in conjunction with the 1904 publication of The Marvelous Land of Oz.

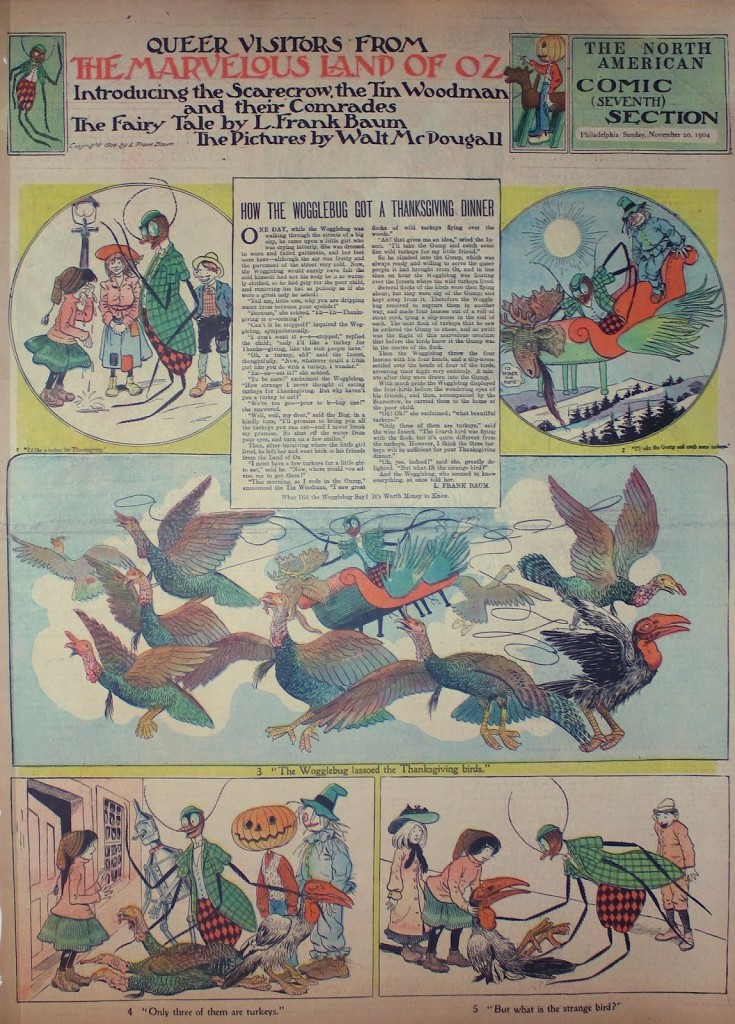

The comic was called Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz and its tie to the latest addition to the Oz book series was obvious, a calculated bid to acquire new readers and a form of advertising that harkens forward to the media tie-ins for today’s block-buster movies. Queer Visitors was written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by Walt McDougal, better known as a political cartoonist. It ran for 27 episodes from August 1904 to February 1905, in newspapers throughout the country, THE REVELATOR being one notable venue. Both Baum and McDougal expressed admiration for the quality and fidelity of the feature’s reproduction in THE REVELATOR, and it was comic clippings from its pages that they passed on to friends.

Although beautifully rendered — and the Sunday comics were sumptuous visual treats at the turn of the century—Queer Visitors cannot be considered that influential on the comics medium. Queer Visitors occurred at a time when the comic strip was still in the throes of inventing itself and the presentation owed more to book illustration than what we would now consider a comic strip. There was a sense of continuity in the misadventures of Dorothy and her friends but each Sunday story was self-contained and published as a solid block of text by L. Frank Baum surrounded by McDougal’s illustrations. Word balloons were used occasionally but these were not essential to advancing the story.

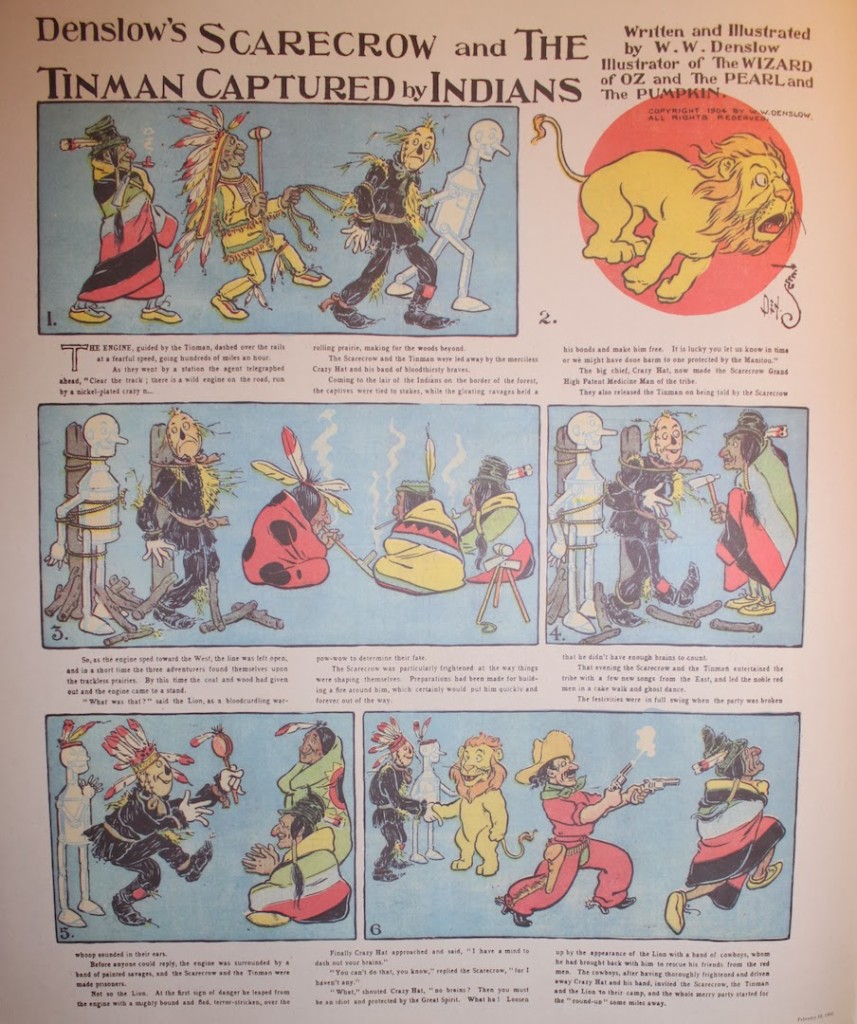

Interestingly, a second Sunday comic strip featuring the Oz characters ran almost coincidentally with Queer Visitors. This strip, Scarecrow and the Tinman, was written and illustrated by the original artist for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, W. W. Denslow. Denslow shared the copyright with Baum for characters from The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and produced his own comic feature after their falling out. Scarecrow and the Tinman ran for only 13 episodes from December 1904 to March 1905. It was never featured in THE REVELATOR, comics editor Solomon Thoreau reportedly referring to it as ‘infantile’.

Baum probably never intended to continue his comic strip beyond 1905. He had other dreams, other books to write, and the strip had served its purpose of introducing a new audience to the Land of Oz. How could he have predicted the unsuspected turns of events that would forge a new friendship and a new direction? Baum had a lifelong love for all aspects of publishing, serving as a newspaper editor for The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer as well as printing an amateur newspaper called The Rose Lawn Home Journal. He recognized quality and this no doubt inspired his Christmas letter of 1904 to THE REVELATOR. The glowing letter made its ways into the hands of Solomon Thoreau who, encouraged by its closing lines, “Oz and THE REVELATOR were made for each other,” responded with an admiring letter of his own. The two men’s friendship was cemented by the discovery that both had been born in the village of Chittenango, New York. Baum and Thoreau never met but they maintained an epistolary friendship that lasted until Baum’s death in 1919.

In conjunction with the publication of Ozma of Oz in 1907, Baum taking advantage of what he had learned from the Queer Visitors strip, approached Thoreau with a radical new idea: a daily comic strip featuring his characters. It’s uncertain who first suggested this would be exclusive to THE REVELATOR but the timing was opportune. THE REVELATOR had recently transitioned from a weekly to a daily in response to the demands of its ever-increasing audience. Both Baum and Thoreau saw the benefits of the arrangement. Baum would benefit from the association with one of the nation’s most trusted news sources. THE REVELATOR foresaw the latent possibilities in the new medium, recognized Baum’s genius, and had the funds to recompense him in appropriate fashion.

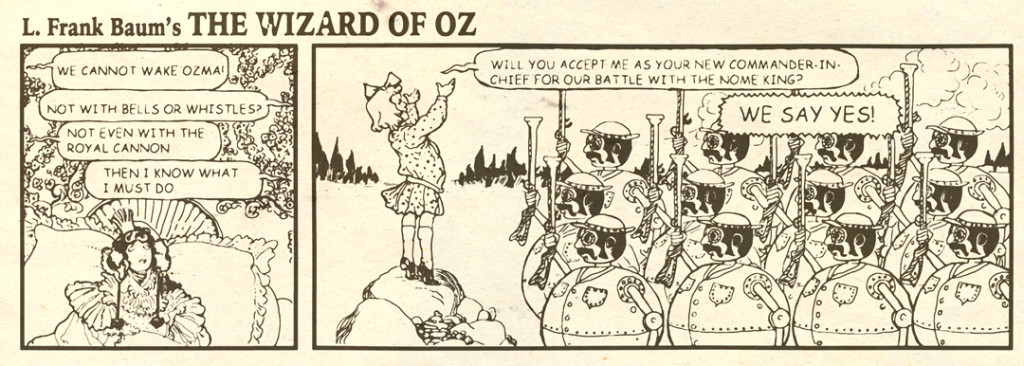

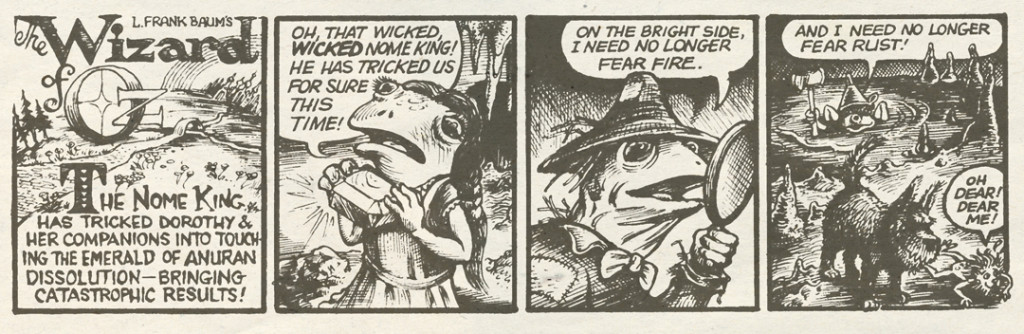

Baum, employing the same approach he pioneered with Queer Visitors, had the events of his new strip immediately follow those of his latest book, Ozma of Oz. But the similarity ended there. He made no attempt to translocate his characters to the United States but instead let them remain in Oz, the new adventures — and what grand adventures they were! — seamlessly picking up where Ozma of Oz ended. The evil Nome King, already introduced in Ozma of Oz, was Dorothy’s chief antagonist in the newspaper strips.

The new strip was titled L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, emphasizing both creator and the inaugural volume in the series. Baum plotted the adventures and took particular pride in them. The artists were never acknowledged, however, the impression being that the stories were solely the product of Baum’s prodigious talents. Initially, and also serving to maintain the seamless connection to the recent Oz books, the artists aped the distinctive style of John R. Neill. Neill himself may have contributed but remained uncredited. Comic historians still debate whether Neill produced the sleeping Ozma modeled after a drawing by the decadent artist Aubrey Beardsley, an allusion that would have been missed by Baum but might have been appreciated by the more ‘adventurous’ readers of THE REVELATOR.

The influence of Neill persisted for well over a year, but the artists gradually asserted more individuality, a process accelerated by the positive response of THE REVELATOR’s readers. Baum relished this response, as documented in his letters to Thoreau, for it placed a primacy on the storyteller rather than the artist. Baum was inspired to new heights of creativity, wherein he took full advantage of the medium and laid the foundations for the adventure comic that would influence so many subsequent newspaper strips. The titular character in Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie along with her dog Sandy owe much to Dorothy and Toto. Similarly, Milton Caniff in Terry and the Pirates introduced a young protagonist, this time male, and thrust him into the exotic locale of China where he conflicted with the Dragon Lady, a female proxy for the Nome King. Although perhaps the least similar in content, Chester Gould has often acknowledged his debt to Baum’s Wizard of Oz in his creation of Dick Tracy, citing in particular the fanciful menagerie of characters that inspired his own rogue’s gallery.

One of the central mysteries of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz is what precipitated its transition from an adventure comic to a gag strip in 1913. Was it orchestrated by the strip’s creators and their desire to blaze new artistic directions, having already established the precepts of the adventure strip? Was it the result in changing publication schedules? THE REVELATOR retreated from a daily to a weekly and then to an indeterminate schedule that rankled its ardent fans, THE REVELATOR being one of the few voices of reason as nations dissolved into chaos on the brink of World War I. Regardless of the impetus, the new direction was to prove equally influential, establishing the template for a whole new style of strip and one appropriate to the ever-decreasing attention span of the turbulent modern world.

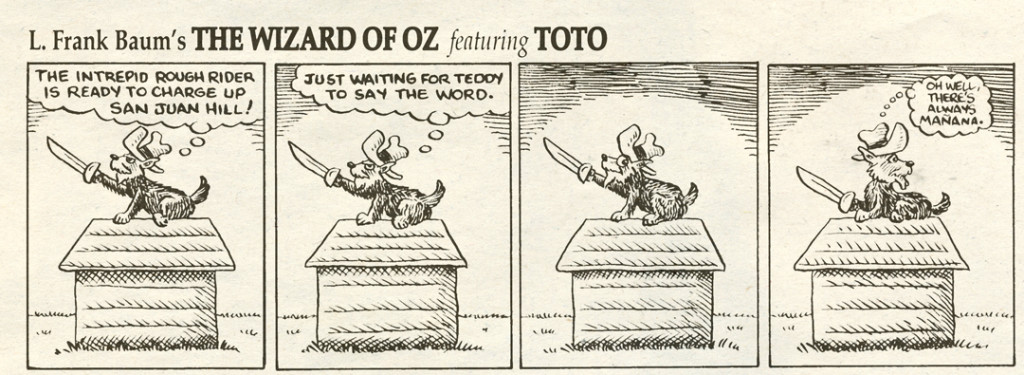

The final days of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz are of particular interest, so closely are they intertwined with the U.S. and its participation in World War I. By this time the strip had embraced its lovable pooch Toto, long a favorite with readers, and granted him both titular emphasis and a mental life that dwarfed that of the human characters. It’s no surprise that Charles Schultz declared Toto the spiritual godfather to his own Snoopy, making reference to these late era Baum strips as inspiration.

But why the sudden political references to the Rough Riders in the last weeks of the strip’s run? Shortly after the U.S. entered World War I, Theodore Roosevelt received approval from Congress to raise four divisions to fight in France, to essentially reestablish the Rough Riders that had proved so effective during the Spanish-American War. Final approval, however, still required permission from President Woodrow Wilson. Having heard that President Wilson read THE REVELATOR with his morning breakfast, Roosevelt approached Baum with the suggestion that he incorporate the Rough Riders into the Oz strip, no doubt thinking this would reinvigorate both the public’s and the president’s support of the Rough Riders. Roosevelt did not take into account the requirements of a gag strip, which by its very nature will inspire laughter, gentle or otherwise, for its subjects. According to two of Roosevelt’s officers, Seth Bullock and James Garfield, Roosevelt was outraged that the strips suggested he and his volunteer corps were more interested in siestas than training or battle.

On May 19, 1917, President Wilson sent Roosevelt a telegram refusing him permission to raise his new divisions of the Rough Riders. Roosevelt assigned blame to Baum and THE REVELATOR, blind to the schisms he had already opened in the Republican Party and his own denouncements of Wilson’s foreign policy. Although no concrete evidence has been uncovered, the sudden termination of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz strip within two weeks of the telegram exchange between Roosevelt and Wilson is clearly suggestive of cause and effect. As is the fire that destroyed two of THE REVELATOR warehouses containing issues from that period. We are only left to wonder what further permutations of the strip might have been wrought in the ensuing years if it had persisted. We are only left to regret the masterpieces we might now be reading in the Funny Pages as a result of its immeasurable influence. These remain to be discovered by adventurous readers who pursue their own dream journeys to the Land of Oz.

Belgian-born Marie Geraud has written extensively about comics and sequential art. She provided the French language annotations to The Gnome King of Oz, by Ruth Plumly Thompson, the twenty-first in the Oz book series, as well as to Richard Corben’s Den in Métal hurlant (omnibus edition). Marie Geraud thanks Chad Woody and Jim Siergey for access to their personal collections of Oz memorabilia. This essay was translated from the French by the Revelator staff.

You must be logged in to post a comment.